Books

Alien State

Sayaka Murata’s second novel to be translated into English, Earthlings, is as quirky as her debut – but a lot more disturbing

Alien State

Sayaka Murata’s second novel to be translated into English, Earthlings, is as quirky as her debut – but a lot more disturbing

Culture > Books |

Alien State

October 21, 2020 / by China Daily Lifestyle Premium

Just released in an English translation, Earthlings is Sayaka Murata’s 2018 follow-up to her wildly popular novel Convenience Store Woman. Set in Japan, it tells the story of two children (Natsuki and Yuu) who believe they’ve come from outer space. Both have been separated from their families and treated badly by the people who should care for them. In Natsuki’s case, her mother prefers her sister and she’s been sexually abused by one of her teachers. Her best and only friend, is Piyyut, a soft toy hedgehog, who tells Natsuki he’s an alien from the planet Popinpobopia.

Once a year, Natsuki and her family holiday in the mountains of Akishina, where Natsuki meets up with her equally displaced cousin, Yuu. But when the two try some sexual experimentation and are caught by Natsuki’s mother, father and sister, they’re forbidden from seeing each other again.

Years pass. Natsuki, now 31, meets Tomoya over a digital marriage site on which users can stipulate “no sex” and “no children”. She sees him three times and marries him, despite the fact she neither loves him nor sleeps with him: “We ate our meals separately. We also washed our clothes and underwear separately – me on Saturday, he on Sunday. We took turns to clean the toilet every weekend.”

They’re connected by their shared malice towards society (or what they call “the Factory”), in which they feel trapped, like cogs in the machinery whose only role is to produce children. “I was expected to become a component for the Factory. It was like a never-ending jail sentence. Everyone was brainwashed by the Factory. They used their reproductive organs for it,” bemoans Natsuki. “Deep down, everyone hates work and sex,” says Tomoya. “They’re just hypnotised into thinking that they’re great.” Tomoya then gets fired, so the pair head to Akishina and, by coincidence, meet Yuu.

What follows – murder, landslides and some inventive dining choices – make for disturbing and unexpected reading. Without proper supervision, Sayaka sometimes lapses into melodrama in her prose. But as in Convenience Store Woman, Murata’s storytelling voice is deadpan and linear. Grotesque in parts, laugh-out-loud funny in others, Earthlings makes for gripping reading. ![]()

Quartet to Read

From a portrait of contemporary working-class womanhood in Japan to the rules of contagion, and from unlocking the secrets of the universe to the meaning of clothes and how we wear them, here are four titles to enliven your stay-at-home experience

Quartet to Read

From a portrait of contemporary working-class womanhood in Japan to the rules of contagion, and from unlocking the secrets of the universe to the meaning of clothes and how we wear them, here are four titles to enliven your stay-at-home experience

Culture > Books |

Quartet to Read

September 9, 2020 / by China Daily Lifestyle Premium

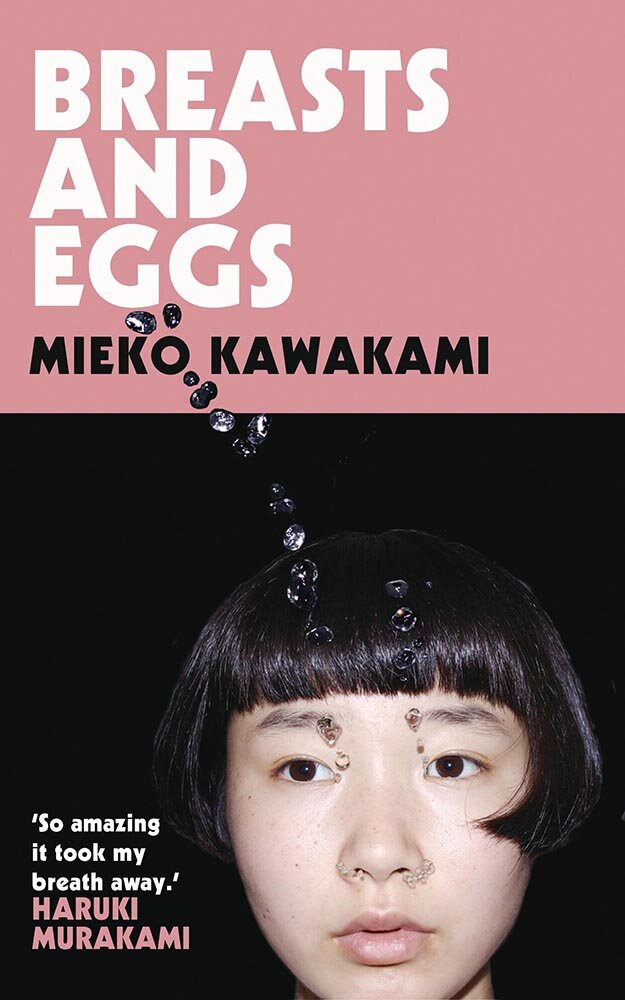

BREASTS AND EGGS

Mieko Kawakami

You know you’re about to read something special when renowned writer Haruki Murakami calls the author his favourite young writer in Japan. So it is with Mieko Kawakami’s quirkily titled Breasts and Eggs. On a hot summer’s day, we meet three women: 30-year-old Natsu, her elder sister Makiko and Makiko’s teenage daughter Midoriko. An ageing hostess losing her looks, Makiko travels to Tokyo for breast enhancement surgery. She’s accompanied by Midoriko, who has recently stopped speaking, finding herself unable to deal with her changing body and her mother’s self-obsession. Her silence dominates Natsu’s rundown apartment, providing a catalyst for each woman to grapple with their anxieties and relationships with one another.

Eight years later, we meet Natsu again. Now a writer, she makes a journey back to her native city, returning to memories of that summer as she faces her own uncertain future. All of this parallels the real-life story of Kawakami, who worked as a hostess, a bookseller, a singer and blogger before publishing her first full-length novel, 2010’s Heaven, to great acclaim.

Breasts and Eggs paints a radical and intimate portrait of working women’s lot in Japan, in a society where the odds are stacked against them. Kawakami is indeed a major new international talent to watch. (Picador)

UNLOCKING THE UNIVERSE: EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO TRAVEL THROUGH SPACE AND TIME

Stephen & Lucy Hawking

“We can boldly go where no one has gone before; who knows what we will find and who we will meet?” remarked the late Stephen Hawking towards the end of his life. Given the missions to Mars taking place this year and ambitious projects underway to land craft on Jupiter’s moons, this book makes the perfect primer for children and adults alike – though the book suggests ages nine to 17. It’s on everything we ever wanted to know about the universe but were too afraid to ask. How did it all begin? What does it take to put humans on Mars and have them survive? What would you do if you had the opportunity to travel through space and time? This collection of up-to-the-moment essays and mind-blowing facts by the world’s top scientists, including the late Professor Hawking, is curated by his daughter Lucy. It’s stunning in its scope, ambition and enlightenment. Among its many revelations, we’re now just decades away from becoming a multi-planet species. (Puffin)

THE RULES OF CONTAGION: WHY THINGS SPREAD – AND WHY THEY STOP

Adam Kucharski

It’s difficult to imagine a more timely title than this authoritative work. Our lives are shaped by outbreaks – of disease, of misinformation, even violence – that appear, spread and fade away with bewildering speed. To understand them, we need to learn the hidden laws that govern them. From “superspreaders” who might spark a pandemic or bring down a financial system to the social dynamics that make loneliness catch on, The Rules of Contagion offers compelling insights into human behaviour and explains how we can get better at predicting what happens next. Along the way, Adam Kucharski explores how innovations spread through friendship networks, what links computer viruses with folk stories, and why the most useful predictions aren’t necessarily the ones that come true. Much to contemplate as we limp our way through COVID-19... (Wellcome Collection)

CLOTHES… AND OTHER THINGS THAT MATTER

Alexandra Shulman

The former UK Vogue editor explores the meaning of clothes and how we wear them. From the little black dress to the white shirt and the bikini, she takes pieces of clothes and examines their role in her own life and the lives of women in general, touching on issues including sexual identity, motherhood, ambition, power and body image. In the introduction, Shulman writes, “[This] is a book not only about clothes, but about the way we live our lives. From childhood onwards, the way we dress is a result of our personal history. In a mix of memoir, fashion history and social observation, I am writing about the person our clothes allows us to be – and sometimes the person they turn us into.” Witty, self-deprecating and often very moving, this book doesn’t require fashionista credentials to enjoy it. (Octopus Publishing Group) ![]()

On the Cusp

A momentous book celebrates famed photographer Henri-Cartier Bresson’s lasting visual legacy in China

On the Cusp

A momentous book celebrates famed photographer Henri-Cartier Bresson’s lasting visual legacy in China

Culture > Books |

On the Cusp

September 9, 2020 / by China Daily Lifestyle Premium

Who knew? Luminary French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson travelled to China in December 1948 at the request of Life magazine. He stayed for ten months and captured some of the most spectacular moments in the country’s history, photographing Beijing in the final days of the Kuomintang and bearing witness to the new regime’s takeover in Shanghai.

Then, in 1958, Cartier-Bresson was one of the first Western photographers to return to China to document the changes that had taken place over the preceding decade. The “picture stories” he sent to the Magnum Photos agency and Life played a key role in Westerners’ understanding of Chinese political events. Many of these images are among the most significant shots in Cartier-Bresson’s oeuvre; his empathy with the populace and his sense of responsibility as a witness make them an important part of his legacy.

Henri Cartier-Bresson: China 1948–1949, 1958 allows these historic photographs to be re-examined along with all of the preserved documents (including the photographer’s captions, comments, contact sheets and abundant correspondence) as well as the published versions that appeared in American and European magazines. A welcome addition to any photography lover’s bookshelf, this is an exciting new volume on one of the 20th century’s most important photographers – and required reading for anyone interested in the history of modern China.

Published by Thames & Hudson, 288pp. (thamesandhudson.co) ![]()

Art in the City

Make time for two Tai Kwun Contemporary titles on a pair of the city’s most compelling artists: Chu Hing-wah and Ho Sin-tung

Art in the City

Make time for two Tai Kwun Contemporary titles on a pair of the city’s most compelling artists: Chu Hing-wah and Ho Sin-tung

Culture > Books |

Art in the City

August 19, 2020 / by China Daily Lifestyle Premium

In case you missed the launch and reading of Chu Hing-wah’s Hong Kong Art Story earlier this year and Ho Sin-tung’s Future Perfect Tense, now’s the perfect time to discover this uplifting pair of Tai Kwun Contemporary-published titles, currently selling at Kelly & Walsh bookshops in Hong Kong. They’re part of Hong Kong Art Stories, a book series commissioned by Tai Kwun Contemporary and created by Caroline Chiu Studio. The books were originally intended as curatorial and educational tools for children to encourage greater appreciation for Hong Kong’s art history as told through the eyes of local artists, but their wonder is equally appealing to adults with aesthetic predilections.

Local illustrators Hilarie Hon and Sushan Chan have interpreted Chu’s life story through his paintings and the evolution of his painting style. Chu, now in his 80s, is still painting scenes that capture the joy of living in Hong Kong. He trained as a psychiatric nurse in London in 1965 and returned to work as a staff nurse at Castle Peak Psychiatric Hospital in Tuen Mun from 1968 to 1989. The artist has used psychiatric patients as subjects for his paintings; their social isolation and mental anguish are captured in scenes of folk-like simplicity and stark poignancy.

Since retiring from nursing in 1992 (the same year he was named Painter of the Year by the Hong Kong Artists’ Guild Association), Chu concentrated more on capturing the realities of Hong Kong life, including the effects of rapid urbanisation in places such as the New Territories. He’s still active and most recently held a show at Johnson Chang’s Hanart TZ Gallery.

In a very different vein, Ho, a graduate of the Department of Fine Arts at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, reflects on the influences that have shaped her as child and an artist in Future Perfect Tense. Her magical and occasionally dark book invites viewers to ponder what makes for potentially scary or frightening viewing.

Ho believes in ghosts and expresses some of her deep fears in her pencil, graphite and watercolour drawings, which she combines with found and ready-made images such as maps, charts, stickers, rubber stamps and timelines. It brings to mind the works of Maurice Sendak and Tomi Ungerer, but Ho’s pencil drawings of dark gorillas and rabbits enchant the young and the old alike. She nourishes a passion for cinema that inspires and infuses much of her work, which has shown at biennales in Shanghai and Seoul.

Isn’t it about time you discovered this dynamic duo? ![]()

Calling Cards

From entertainment to the esoteric, the mystique of tarot continues to influence culture

Calling Cards

From entertainment to the esoteric, the mystique of tarot continues to influence culture

Culture > Books |

Calling Cards

August 5, 2020 / by China Daily Lifestyle Premium

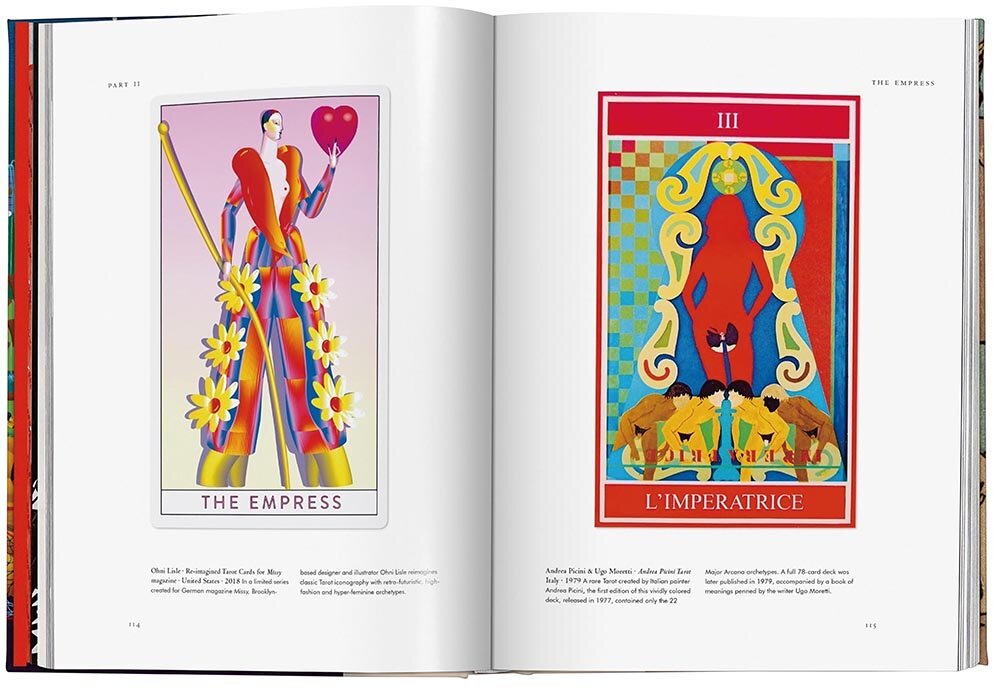

When it comes to the subject of tarot cards, there are as many narratives for its origins as there are for the innumerable readings that spring from its visual references and codes. Could it be traced back to Egyptian hieroglyphics? Is it connected to the Hebrew alphabet and the Jewish tradition of kabbalah? Or were they a form of divination invented by the Romani people?

What we do know for now is that the Visconti-Sforza is the oldest set of surviving tarot cards, which were created for the Duke of Milan’s family around the year 1440. Illustrated with figures paraded in pageants, such cards were used to play the game tarocchi (similar to modern-day bridge) by nobles and others. Later, the French renamed it as tarot, but it wasn’t until the 18th century, when the occult became fashionable and oft referenced in literature, that tarot cards took on mystical overtones. In the early 1900s in America, the cards garnered a cult following.

For many in the West, tarot exists in the shadowy space of our cultural consciousness, a metaphysical tradition assigned to the dusty glass cabinets of the arcane. Its history, long and obscure, has been passed down through secret writings, oral tradition, and the scholarly tomes of philosophers and sages. Hundreds of years and hundreds of creative hands – with mystics and artists often working in collaboration – have transformed what was essentially a parlour game into a source of divination and a system of self-exploration, as each new generation has sought to evolve the form and reinterpret the medium.

And particularly creative types. The powerful influence of tarot as a muse has influenced artists such as Salvador Dalí and Niki de Saint Phalle, as well as numerous contemporary artists from around the world, who have embraced the medium for its capacity to push cultural identity forward.

Though he seems a natural fit, Dalí’s connection is most surprising; the surrealist was approached by James Bond producer Albert R Broccoli to create a tarot deck for a scene in the 1973 film Live and Let Die, but it never appeared in the film. (The props were needed for the character of Solitaire, played by Jane Seymour, a psychic working for a menacing drug lord.) In the 78-card deck that Dalí produced, the artist uses himself and his wife, Gala, as mystical figures. The scenes feature the Spanish surrealist’s signature motifs – butterflies, ants, roses and dissected faces.

Today, the influence of tarot on art and fashion is widespread, as the material world channels the occult in everything from Alexa Chung’s tarot-themed T-shirts for her spring/summer 2019 collection to Etro’s allegorical spring/summer 2018 menswear collection, and to Maria Grazia Chiuri’s striking tarot-influenced accessories and capsule collection for Dior in 2017. Chiuri acknowledged that her interest in the occult aesthetic was sparked by the works of Saint Phalle, who was inspired by witches, dragons, magicians and the angel of temperance.

Trace the hidden history and artistic expression of tarot, from the medieval to the modern day, in the first volume of Taschen’s Library of Esoterica, a series documenting the creative ways we strive to connect to the divine. Artfully arranged, this compendium gathers more than 500 cards and works of original art from around the world in the ultimate exploration of a centuries-old visual form. Two-thirds of the images are being published for the first time. It makes for informative and inspiring reading – and viewing.

Divine Decks: A Visual History of Tarot by Jessica Hundley. Published by Taschen. ![]()

Summer Reads

While lockdown may have affected our ability to travel and work, it hasn’t slowed the pace of must-read new books. Whether we can or can’t indulge the habitual pleasures of escapist reading on the beach, here’s an eclectic and electric quartet of fiction(including one for the kids) to satiate and surpass all literary leanings

Summer Reads

While lockdown may have affected our ability to travel and work, it hasn’t slowed the pace of must-read new books. Whether we can or can’t indulge the habitual pleasures of escapist reading on the beach, here’s an eclectic and electric quartet of fiction(including one for the kids) to satiate and surpass all literary leanings

Culture > Books |

Summer Reads

July 8, 2020 / by China Daily Lifestyle Premium

WASTE TIDE

Chen Qiufan’s cutting-edge, near-future sci-fi novel is about as prescient as writing gets. It’s a story based on a real-world Chinese town that recycled the world’s electronic waste. In the novel, the waste dump is called Silicon Isle, and it becomes the lifeblood of desperate workers from around China who – despite the toxic hazards, environmentalists’ attacks, long hours and pitiful wages – all want to work their way out of poverty. Meanwhile, relationships are formed between friends and exploiters (and there’s a fine line between the two) against the troubling and accelerating backdrop of biological warfare, artificial intelligence and virtual reality. Simply stunning.

SLIME

British author and former comic actor David Walliams has firmly established himself as his generation’s Roald Dahl, with an ability to pen fantastically funny and engaging tales, all illustrated by Dahl’s former artist, Tony Ross. Slime is a tiny island that’s home to a large number of nasty grown-ups who run the schools, parks, shops and even the ice cream van, and they all make the little ones’ lives miserable. Something needs to be done. But, who is brave enough to take on the nastiest adult of them all – the island’s owner, Aunt Greta Greed? Meet Ned, the boy wonder with a special power: slimepower!

IF I HAD YOUR FACE

Frances Cha’s debut novel is set in contemporary South Korea, where it’s estimated that one in three women have plastic surgery before the age of 30. Cha uses this reality to portray the tale of four young women from the same apartment block who strive to “beautify” themselves in the hopes of getting ahead. Along the way, the women nurture a strength, spirit and resilience from the friendship they develop, but the results of their “makeovers” meet with mixed success – or a lack of it. It’s an eye-opening depiction of Korean society and its deep-seated inequalities, but one which Cha, a former Seoul-based travel and culture editor for CNN, tells with vigour and panache.

LAST TANG STANDING

Like all good Chinese children, Andrea Tang is doing her best to fulfil her mother’s plans for her life: she’s on track to become partner at a top Singapore law firm, she has a beautiful apartment and she’s got the perfect hubby-to-be boyfriend. But a highly attractive new lawyer is trying to steal her promotion, she’s maxed out her credit cards and her boyfriend’s gone walkabout. Cue multiple dating problems. Funnier and deeper than Kevin Kwan’s Crazy Rich Asians – and written with a wit, verve and tenderness that Kwan’s novel lacked – Lauren Ho’s debut is a dazzlingly dashing rom-com. ![]()

Sole Survivor

Mary Shelley’s little-known 1826 novel The Last Man, concerning a 21st-century plague, couldn’t be more prescient

Sole Survivor

Mary Shelley’s little-known 1826 novel The Last Man, concerning a 21st-century plague, couldn’t be more prescient

Culture > Books |

Sole Survivor

May 6, 2020 / by China Daily Lifestyle Premium

“Many of those who remained secluded themselves; some had laid up stores which should prevent the necessity of leaving their homes – some deserted wife and child, and imagined that they secured their safety in utter solitude. Such had been one man’s plan, and he was discovered dead and half-devoured by insects, in a house many miles from any other, with piles of food laid up in useless superfluity. Others made long journeys to unite themselves to those they loved, and arrived to find them dead.”

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley is principally known for two reasons: She was the wife of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and she was the author of the 1818 novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. The fame she attained for the latter far surpassed the former. However, little known to many readers today, she wrote at least five other books, novellas, dramas and short stories, along with travel books and biographies.

In the wake of the current global pandemic, her novel The Last Man merits swift reappraisal. Published in 1826, it’s a shockingly relevant post-apocalyptic science-fiction tale that tells the story of a 21st-century plague and its solitary survivor. He’s Lionel Verney, living in 2073 and, by the novel’s end, 2100.

Largely an autobiographical figure for Mary Shelley, Lionel becomes the last man alive on Earth and the story is told through him. After a series of travails across three chapters, he resolves to live the rest of his life as a wanderer of the vacant continents of Europe and Africa, befriending a sheepdog along the way.

Shelley had been forbidden from publishing a biography of her husband during her life by her father-in-law, so she memorialised him in The Last Man in the utopian figure of Adrian, Earl of Windsor, who befriends Lionel and leads his followers in search of natural paradise, but dies when his boat sinks in a storm. The character of Lord Raymond, who leaves England to fight for the Greeks and dies in Constantinople, is based on Lord Byron.

Declared one reviewer on the book’s launch: “The offspring of a diseased imagination and of a most polluted taste.” Others derided the work as being “sickening” and full of “stupid cruelties”. Shelley called it one of her favourites. Contemporary novelist Muriel Spark wrote that Shelley “created an entirely new genre, compounded… of the domestic romance, the Gothic extravaganza and the sociological novel.”

While the plague in The Last Man might be metaphorical – the end of an empire, the Romantic traditions and humanism – the novel contains much scientific exactitude concerning the development of smallpox vaccine and 19th-century theories about the nature of contagion. Concluding with the picture of Earth’s solitary inhabitant, Shelley infers that the condition of the individual is essentially isolated and tragic. “Yes, I may well describe that solitary being’s feelings, feeling myself the last relic of a beloved race, my companions extinct before me,” she wrote in her journal in 1824. Prescient, indeed. ![]()

Culinary Marvels

The 100 Top Chinese Restaurants of the World guide publishes its second edition, giving the reader a chance to explore Chinese cuisine all over the planet

Culinary Marvels

The 100 Top Chinese Restaurants of the World guide publishes its second edition, giving the reader a chance to explore Chinese cuisine all over the planet

Culture > Books |

Culinary Marvels

May 6, 2020 / by Philippe Dova

Dong Shun Xiang’s pyramid of braised sliced pork

An author, lawyer and wine critic, Ch’ng Poh Tiong writes about cuisine from a cultural and historical point of view. In his 100 Top Chinese Restaurants of the World 2020, just published as its second edition, the restaurants aren’t ranked. However, there are accolades for Restaurant of the Year, Dish of the Year (for Dong Shunxiang at Wei Zhuang Hangzhou and his braised sliced pork pyramid), Chinese Cuisine Ambassador of the Year (for Alfred Leung Chi-wai, the founder of Imperial Treasure Restaurant Group), and separate lists for the Top 10, Top 20 and Top 30.

What’s fascinating about this book is that it explores Chinese restaurants around the world –and not just the ones you’d expect in Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong. Among the cities represented are New York, London, Paris, Mumbai, Yokohama, Bangkok, Ipoh, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, Foshan, Guangzhou, Hangzhou, Yangzhou, Suzhou… the list goes on.

Beyond the restaurants themselves, the reader will discover numerous things they may not know: that xiao long bao didn’t originate in Shanghai but was already very popular in Kaifeng during the Northern Song dynasty; that the best char siew may actually be in Malaysia; and that there’s a teahouse in Yangzhou that makes up to 50,000 bao a day. Time to plan a road trip…

Print versions of 100 Top Chinese Restaurants of the World 2020 (in English and Traditional Chinese) are available at 13 major bookshops across Hong Kong, while e-versions (English, Traditional Chinese and Simplified Chinese) are available at 100chineserestaurants.com. ![]()

Running Through Time

Bold designs and epic moments make up the 100-year history of Adidas in a new Taschen tome

Running Through Time

Bold designs and epic moments make up the 100-year history of Adidas in a new Taschen tome

Culture > Books |

Running Through Time

April 15, 2020 / by China Daily Lifestyle Premium

Image above: The Adidas Archive: The Footwear Collection, 644pp, HK$1,300 (taschen.com)

Before there was a glut of designer crossovers that defined the world of sneakerheads and hypebeasts, there were sports shoes that bore the stains, the tears, the repair tape, the grass smudges and the faded autographs of their remarkable sporting historical provenance and individual stories. Many of those were made by Adidas.

Brothers Adolf (“Adi”) and Rudolf (“Rudi”) Dassler made their first pair of sports shoes 100 years ago – and now, hundreds of innovative designs, epic moments and star-studded collaborations later, Taschen presents a review of the iconic sports shoe maker through more than 350 models, some never-before-seen prototypes and one-off originals.

As a way of customising his products to athletes’ specific needs, Adolf Dassler asked them to return their worn footwear, with all the shoes eventually ending up in his attic. To this day, many athletes return their shoes to Adidas, often as a thank-you after winning a title or breaking a world record. That collection comprises the “Adidas archive”, which photographers Christian Habermeier and Sebastian Jäger have been visually documenting in extreme detail for the last decade.

Along the way, we encounter shoes worn by West Germany’s football team during its “miraculous” 1954 World Cup win and those worn by Kathrine Switzer when she ran the Boston Marathon in 1967, before women were officially allowed to compete. Then there are the modern-day wonders, with custom models for stars from Madonna to Lionel Messi, and collaborations with the likes of Kanye West, Pharrell Williams, Raf Simons, Stella McCartney, Parley for the Oceans and Yohji Yamamoto. The book also traces Adidas’s trailblazing techniques, such as its use of plastic waste intercepted from beaches and coastal communities.

With a foreword by designer Jacques Chassaing and insightful texts, each picture tells us the why and how, and conveys the driving force behind Adidas. What we discover goes beyond mere design; in the end, these are just shoes, worn out by users who have loved them. But they’re also first-hand witnesses to our sports, design and cultural history – and a highly fashionable one at that. ![]()

Japan: Past, Present and Future

A sublime anthology of short stories highlights the country’s rich literary traditions, from the darkest of the dark to the poetically poignant, and from the mundane to the uplifting

Japan: Past, Present and Future

A sublime anthology of short stories highlights the country’s rich literary traditions, from the darkest of the dark to the poetically poignant, and from the mundane to the uplifting

Culture > Books |

Japan: Past, Present and Future

October 3, 2019 / by Jon Braun

Equally for readers with limited knowledge of Japanese literature as it is for those well acquainted with various authors from the archipelago, The Penguin Book of Japanese Short Stories, edited by Japanese literary expert and long-time Murakami Haruki translator Jay Rubin, is a brilliant bookshelf addition – and a work that you’ll revisit time and time again.

Among the most prominent authors familiar to non-Japanese audiences are Murakami, who contributes “The 1963/1982 Girl from Ipanema” (1982) and “UFO in Kushiro” (1999) as well as an insightful 22-page introduction, and Mishima Yukio, whose brutally beautiful and ever-shocking work “Patriotism” (1961) espouses a near-obsessive loyalty to the Japanese emperor and an eroticism in the ultimate act of seppuku (ritual suicide), which the writer himself carried out in 1970 after an attempted coup in Tokyo. Other familiar names in the anthology include Natsume Soseki, Tanizaki Junichiro, Kawabata Yasunari and Yoshimoto Banana.

However, with most stories and authors appearing for the first time in English, spanning the years 1898 to 2014, there’s plenty to discover among the 35 works. Smartly organised by theme rather than date, the collection is separated into seven sections. “Japan and the West” kicks off with Tanizaki’s 62-page novella “The Story of Tomoda and Matsunaga”, which seems a strange choice in terms of setting the pace, but things soon kick it up a notch.

The subsequent “Loyal Warriors”, “Men and Women”, “Nature and Memory”, “Modern Life and Other Nonsense” and “Dread” all deliver wonderful tales, with numerous highlights along the way including a pair of vastly different mother-and-daughter tales. Ohba Minako’s pithy feminist parable recasts the Japanese folktale monster yamamba, an eerie old woman living in the mountains who eats humans, as a devoted modern-day wife and mother in “The Smile of a Mountain Witch” (1976). The youngest contemporary author in the anthology, Sawanishi Yuten, contributes the surreal, powerful “Filling Up with Sugar” (2013, published when he was just 27); its narrator is a woman caring for her mother, who has been afflicted with (the fictitious) systemic saccharification syndrome – in short, her entire body is gradually transforming into sugar.

But it’s the ultimate “Disasters, Natural and Man-Made” section that has the most impact. Covering Japan’s major earthquakes in 1923, 1995 and 2011, as well as the atomic bombings of the Second World War, Ota Yoko’s “Hiroshima, City of Doom” (a chapter from her 1948 novel City of Corpses) may just move you to tears with her gruesome, harrowing first-hand experiences as a Hiroshima native on that fateful day in 1945. The anthology concludes with the 2011 nuclear meltdown, culminating in Sato Yuya’s highly disturbing work “Same as Always” (2012), about a mother who makes an unconscionable decision about her baby in the aftermath of the Fukushima radiation – and which is likely to leave you shaken to your core.

Rubin assures readers that, rather than shooting for the big names, “all the works have been chosen because the editor has been unable to forget them, in some cases for decades, or has found them forming a knot in the solar plexus or inspiring a laugh or a pang of sorrow each time they have come spontaneously to mind over the years.” He deserves to be lauded for curating this rich, rewarding selection – here’s hoping it will spark a fresh wave of translated works and a rediscovery of the Japanese classics. ![]()

Falling Superflat

One of the world’s greatest modern novelists, Haruki Murakami, delivers a plodding disappointment with Killing Commendatore

Falling Superflat

One of the world’s greatest modern novelists, Haruki Murakami, delivers a plodding disappointment with Killing Commendatore

Culture > Books |

Falling Superflat

September 4, 2019 / by Jon Braun

When a writer’s fame becomes bigger than his or her publishing house, the essential influence of the editor all but disappears. Take the case of JK Rowling, whose first Harry Potter book (The Philosopher’s Stone, 1997) clocks in at 223 pages for the UK edition; growing in size along with the series’ popularity, the final instalment (The Deathly Hallows, 2007) is nearly triple that, at a whopping 607 pages.

But quantity doesn’t necessarily mean quality, and trimming the fat is necessary for writers whose egos transcend the reader. Unfortunately, Japanese author Haruki Murakami’s latest novel, Killing Commendatore, suffers from this malady and it’s hard to see the appeal of 681 pages of rambling, rehashed themes.

Also a prolific translator and a writer of short stories and non-fiction, Murakami’s first novel since 2013’s Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage blends magical realism with historical fiction (Vienna during the Second World War), opera and art references, and so many of the author’s well-worn motifs that just a few minutes of a Murakami-themed drinking game would put you under the table. Without revealing too many spoilers, don’t be surprised to discover a mysterious woman, a faceless villain, sibling trauma, a dried-up well, a secret passageway to another world, numerous cringe-worthy sex scenes… it all makes for a greatest-hits album minus any semblance of original spin.

A nameless Tokyo-based portrait painter is suddenly divorced by his wife; she cites a dream she had six years before. After a road trip to clear his head, he moves into the remote mountain home of his friend’s father, a famous painter who is battling dementia in an elderly home, and discovers a previously unseen work that depicts the opening murder in Don Giovanni; things take a turn for the strange as the Commendatore from the painting comes alive. Meanwhile, a wealthy neighbour with potentially ulterior motives commissions a portrait, and together they explore the source of a mysterious bell that seems to be coming from the well behind the house, which may be a portal to the underworld…

There are nuggets of brilliance to be found throughout (“The world is full of lonely things, but not many could be lonelier than waking up alone in the morning in a love hotel”), but the journey to get there isn’t rewarding, even for die-hard Murakami fans. With too many disparate ideas and themes, long, drawn-out descriptions of little impact, and a lack of character development, it just feels slow – and the payoff is underwhelming, to say the least. To appropriate a term ordinarily invoked of his famous artist namesake, Takashi Murakami, the work feels “superflat”.

This writer has been a fervent fan of Murakami since the 1990s, but the author’s output in recent times shines more in his short stories (Men Without Women) and his insightful non-fiction (Absolutely on Music: Conversations with Seiji Ozawa). With the exception of 2010’s 1Q84, his full-length novels have tended to weaken. For those new to the author and unafraid of his longer, quirkier novels, a better starting place would be 1985’s Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World or 1995’s The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. Certainly with Murakami, the drive is there, as is the talent – but right now he could use a little literary sorcery or some sharper philosophical stones through which to summon his muse. ![]()