Art

On the Wall

A landmark exhibition explores the influence of Michael Jackson on some of the leading names in the contemporary art world

On the Wall

A landmark exhibition explores the influence of Michael Jackson on some of the leading names in the contemporary art world

Culture > Art |

On the Wall

June 6, 2018 / by China Daily Lifestyle Premium

Image above: Equestrian Portrait of King Philip II (Michael Jackson)(2010) by Kehinde Wiley, from the Olbricht Collection, Berlin

An Illuminating Path (1998) by David LaChapelle

Michael Jackson (1984) by Andy Warhol, from the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC; a gift of Time magazine

When Michael Jackson took the stage at the Motown 25 anniversary show at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium in 1983, he gave a baptismal performance of Billie Jean on live television in what would become his trademark look – the sequin-covered black jacket, rhinestone glove, white socks and black Florsheim loafers. Something seismic shook the pop and dance world ever after.

Four minutes and five seconds into the song, Jackson “moonwalked” – and the world gasped in awe. The move, in which the dancer slides backwards but appears to be walking forwards, marked the biggest musical moment in American pop culture since Elvis Presley graced the stage.

Michael Jackson would have been 60 years old on August 29, 2018; he died of cardiac arrest on June 25, 2009 at his Los Angeles home following a medication overdose administered by his personal physician. Nonetheless, almost a decade after his death, the King of Pop’s legacy shows no signs of diminishing. His record sales, now in excess of one billion, continue to grow, his short films are still watched and his global fan base remains ever loyal.

But there’s a little known aspect of the performer’s history – Jackson has become the most depicted cultural figure in visual art by an extraordinary array of top artists since Andy Warhol first used his image in 1982. Despite Jackson’s significance being so widely acknowledged in matters of music and music videos, dance, choreography and fashion, his singular impact on contemporary art is prodigious, and yet, an untold story.

Read More

Untitled #13 (Elizabeth Taylor’s Closet) (2012) by Catherine Opie

“It is rare that there is something new to say about someone so famous,” says Nicholas Cullinan, director of the National Portrait Gallery in London, which will stage the exhibition Michael Jackson: On the Wall over the summer, starting on June 28. “It will open up new avenues for thinking about art and identity, encourage new dialogue between artists, and invite audiences interested in popular culture and music to engage with contemporary art.”

On the Wall, produced with the cooperation of the Michael Jackson Estate, brings together the works of more than 40 artists, which are drawn from public and private collections, including new works made especially for the exhibition. And extraordinarily for someone so publicly exposed and examined as Jackson, the majority of the pieces, both old and new, will be little known to their audience.

The tantalising roster of featured artists includes some of the most important contemporary figures along with emerging talent. They range from Andy Warhol, Isaac Julien, Candice Breitz, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Isa Genzken, Gary Hume, Rashid Johnson and David LaChapelle to Yan Pei-Ming, Kehinde Wiley, Catherine Opie, Rita Ackermann, Hank Willis Thomas and Jordan Wolfson.

Warhol, who had several chance meetings with the singer, wrote of his depiction, Michael Jackson 23, in his diaries. He created the portrait for a Time magazine cover in March 1984, marking the release of Jackson’s album Thriller. “I finished the Michael Jackson cover,” he writes. “I didn’t like it, but the office kids did. Then the Time people came down, about 40 of them, and they stood around saying that it should increase newsstand sales. The cover should have had more blue, but they wanted this style.”

Wind (Michael/David) (2009) by Isa Genzken, from the Hessel Museum of Art at Bard College, New York

Genzken, on the other hand, sees Jackson as a modern-day equivalent of David by Michelangelo. “David is what Michael Jackson always wanted to be like – all these cosmetic operations,” she says. “He wanted to be the most beautiful man in the world.” Her work is like an homage to Jackson, she explains. “It’s the whole package, the whole thing. The way he talks, the way he moves, the way he does things. It’s the admiration I have for him. It’s the whole that is attractive to me.”

On the Wall will not only explore why so many artists have been drawn to Jackson as a subject, but why he continues to loom so large in our collective cultural imagination. The project will also be accompanied by a scholarly publication with essays by Cullinan, Pulitzer Prize-winning cultural critic Margo Jefferson and British author Zadie Smith.

As befits a man who toured the world, On the Wall, which finishes its stint in London on October 21, will travel to the Grand Palais in Paris (November 2018 to February 2019), the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn, Germany (March to July 2019) and the Espoo Museum of Modern Art in Espoo, Finland (August to November 2019). Get ready to leave that nine to five up on the shelf – and just enjoy yourself.

Michael Jackson: On the Wall runs from June 28 to October 21, 2018 at the National Portrait Gallery. (npg.org.uk/michaeljackson) ![]()

Images: Courtesy of the artist (An Illuminating Path); courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles (Untitled #13); courtesy of Neugerriemschneider, photo by Jens Ziehe (Wind (Michael/David)); courtesy of Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York (Equestrian Portrait of King Philip II (Michael Jackson))

Back to top

Art House

Acclaimed Japanese architect Kengo Kuma’s tranquil Zhi Art Museum in Xinjin, near Chengdu, is a thing of beauty and wonder

Art House

Acclaimed Japanese architect Kengo Kuma’s tranquil Zhi Art Museum in Xinjin, near Chengdu, is a thing of beauty and wonder

Culture > Art |

Art House

May 23, 2018 / by Sonia Altshuler

It’s no small feat to be one of Japan’s most acclaimed and versatile architects. But that’s Kengo Kuma for you – in hot global demand and constantly working. His mantra has always been to “recover the tradition of Japanese buildings and to reinterpret these traditions for the 21st century.” In Tokyo, construction has recently begun on his design for the new National Stadium for the 2020 Olympics and he’s building a 13-storey luxury hotel in Ginza, not far from where he built the Tiffany & Co boutique. His rate of work in Japan is matched by numerous projects around the globe: a new Japanese restaurant, Ta-ke, in Hong Kong; mixed-use skyscrapers in Vancouver; a hotel in Paris; a maritime museum in Brittany, France; and a Hans Christian Andersen museum in Odense, Denmark. And of course, he’s also worked extensively in China.

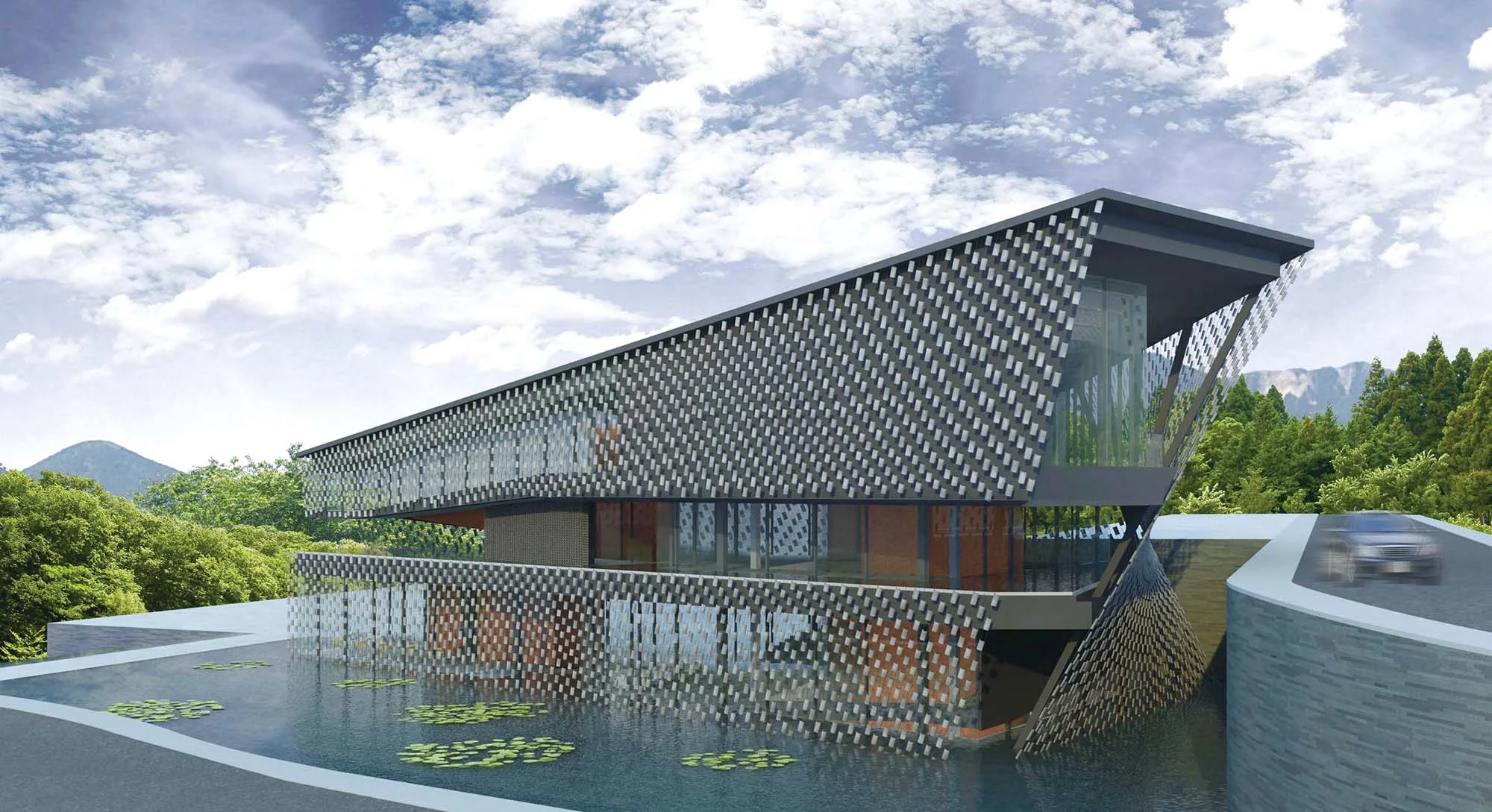

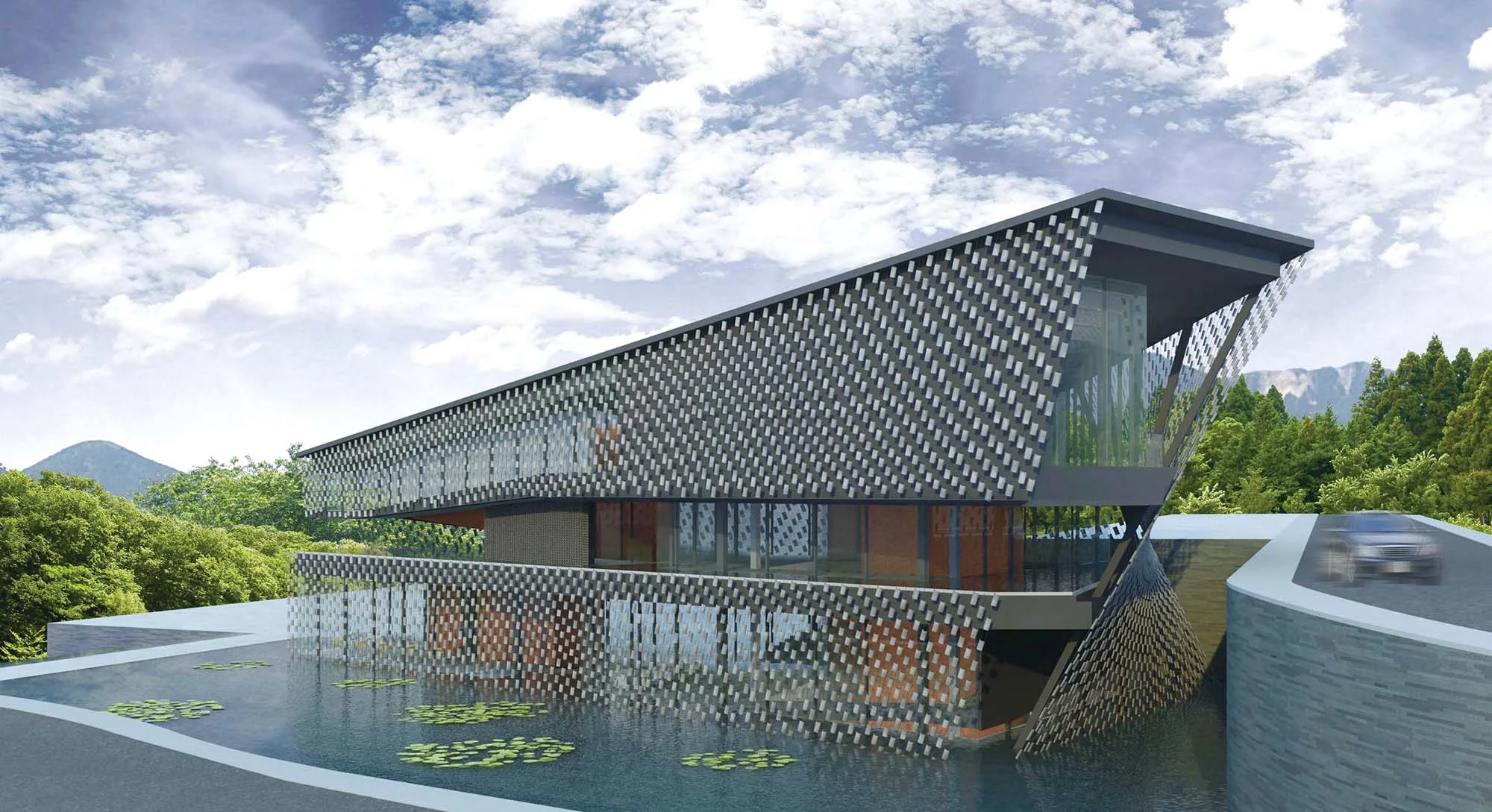

Located at the foot of Chengdu’s Laojunshan in the southwestern Chinese province of Sichuan, the Zhi Art Museum is classic Kuma. Modernist austerity blends with an undulating landscape of mountains and rivers, reminiscent of classical Chinese paintings. The stunning structure uses brick tiles, a traditional local material, which hang and float tantalisingly in the air. Indeed, the museum has the feel of taking a stroll through a garden, with direct sunlight blocked by the tiles and the light opening up in slats. The upper floor affords a paramount view of Laojunshan itself.

Such serene architecture brings to life the beauty and tranquillity of zen – or in this case, Taoism – and the museum bears the hallmarks of Kuma’s signature design ethos, with the Eastern philosophy of learning from nature, all the while combining technological advancements with an innovative use of materials.

Read More

In this case, the main components are light and water – the latter in the form of a large pond, which extends to the exploration of the natural materials throughout, as the architecture organically harmonises with its surrounding elements. The tranquil flow and soft movements surrounding the entirety of the structure allow for contemplation and evoke the notions of eternity through its unity with nature. Kuma constructed it all in line with the core concept, which is based on three principles: universality, insight and innovation.

Kuma’s Zhi Art Museum is enhanced by an exhibition launch in the space. Curated by Zhang Ga and on show until August 12, Open brings a highly idiosyncratic body of work by nine artists. Particularly notable is the monumental installation Pneuma Fountain in front of the museum; Chico MacMurtrie and Amorphic Robot Works’ latest inflatable robotic sculpture interprets the overarching theme of “open” as a contemplative experience of movement, air, light and architecture.

The main gallery houses Zhang Peili’s enigmatic A Standard, Uplifting and Distinctive Circle Along with its Sound System. Participation in this Duchampian installation is delegated to an automata operated via software manipulation. Get ready to be awed, but don’t forget that a visit to Kuma’s elegant Zhi Art Museum is an artwork on its own.

![]()

Image: © Zhi Art Museum, 2018

Back to top

New Discoveries

Long hidden in the shadows of his European and American counterparts, the late Cuban-Chinese-Congolese painter Wifredo Lam is finally stepping into the light

New Discoveries

Long hidden in the shadows of his European and American counterparts, the late Cuban-Chinese-Congolese painter Wifredo Lam is finally stepping into the light

Culture > Art |

New Discoveries

May 23, 2018 / by Kitty Go

Image above: C'est Moi (Le Sacré), 1962

Le Repos du Modéle (Nu), 1938

There’s a belief in certain art circles, as Magnus Renfrew mentions in his 2017 book Uncharted Territory: Culture and Commerce in Hong Kong’s Art World, that there is “a need for institutions of global credibility outside the context of Europe and America to provide a non-Western view of the world.”

Mathias Rastorfer of Galerie Gmurzynska is among those who have firmly backed this idea for many years. “I think part of the task I set for myself as a global gallery is to do something that is specific – to contribute to something that hasn’t been done, has been overlooked or can be rediscovered from the past,” he says.

One artist that he thinks fits this bill – particularly in being ahead of his time and in embodying the new direction of art globalisation – is the late Cuban-Chinese-Congolese artist Wifredo Lam (1902–1982), who was primarily based in Paris.

Lam’s work featured as part of the Kabinett series at Art Basel in Hong Kong in March. The concept of Kabinett is for selected galleries to have curated or themed exhibitions worthy of museums or, in the case of Lam at Gmurzynska, a one-man gallery show. Rastorfer explains his international appeal: “In this context, he is the prime example of an artist of global impact with a multicultural background – he had a Chinese father and carried his name, an African mother, he studied in Spain, and lived in France and Italy. In the 1940s, his most famous work, The Jungle, was bought by MoMA [New York’s Museum of Modern Art] after being shown by a French gallery in New York. Lam was against all odds. He was a man of colour with a communist passport from Cuba, yet he travelled actively around the world despite needing a visa for most countries. He was invited to every cocktail party, and feted and supported by many museums. But being a man of colour, he wasn’t allowed into restaurants. His support from the cultural and intellectual elite, led by MoMA and his dealer, Pierre Matisse, showed that even very early on, art was quite separate from the rest of the country.”

Read More

Sans Titre, 1945

Rastorfer recalls a conversation he had in the 1980s with Jean-Michel Basquiat, who was working in the basement of the New York gallery of Annina Nosei. He asked the young artist who his influences were and Basquiat mentioned Lam. Both were men of colour, outsiders in the rarified art world and had island influences in their work – Cuba for Lam, and Haiti and Puerto Rico for Basquiat. And although racial segregation in the US no longer officially existed at the time of Basquiat’s fame, he still complained that, as a black man, no taxi would stop for him at night.

It’s easy to make comparisons between Lam and a household name like Pablo Picasso. The most obvious is between Lam’s The Jungle (1943) and Picasso’s Guernica (1937). Yet a more analytical and critical eye would see the former’s female horses becoming centaurs under the latter’s brush, as well as their shared use of grisaille, a painting technique using only shades of grey. Because Lam had barely any academic art training and a completely different background, his influences of various African, Cuban and voodoo cultures were far outside the norm – which is exactly what Picasso admired and appropriated. “Good artists copy, great artists steal,” the artist famously quipped. “When you think about Picasso and [Georges] Braque, you wonder who influenced who, but it is clear Braque was first. I feel the same way with Lam,” says Rastorfer.

Rastorfer calls Lam “a diamond in the rough” despite the artist having done some 100 exhibitions by the time of his death, including a joint exhibition with Picasso in New York in 1939. The dealer puts it bluntly: “He’s not as famous as Picasso. In the ’40s, he joined other greats in museums, but never held the same position in the art market. If you look at famous figures in early 20th-century art, they are mostly Europeans; Americans came in in the ’60s.” Being non-European and without active representation, Lam lost work and market presence upon his death. In Cuba, however, it’s a different story. Havana’s Wifredo Lam Centre, in a two-storey 18th-century mansion, is one of the primary locations for contemporary art and plays a key role in the city’s biennale.

Gmurzynska officially took over Lam’s estate seven years ago, at a time when his name was popular primarily with Latin-American collectors. According to Rastorfer, Lam was especially popular in Paris in the ’70s and in Miami in the ’80s. He says that today, there is enormous interest from Chinese museums to host shows and there will be other travelling exhibitions with major museums soon.

“Lam’s retrospectives over the last three years at the Tate and the Pompidou Centre have brought his name outside Miami,” says Rastorfer.“From a market point of view, he moved from the Latin-American sales into the Modernist and Evening ones. The most interesting thing about Lam in Asia, for Gmurzynska, is that there is no other classic modern painter in the first half of the 20th century who qualifies as Chinese.”

![]()

Images: Courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska

Back to top

Mathias Rastorfer

Baring It All

A rare nude by maverick Italian painter Amedeo Modigliani is poised to become the world’s second most expensive artwork

Baring It All

A rare nude by maverick Italian painter Amedeo Modigliani is poised to become the world’s second most expensive artwork

Culture > Art |

Baring It All

May 9, 2018 / by Sonia Altshuler

Mad, bad and dangerous to know, and often inebriated on a combination of drugs and alcohol, Italian-born and Paris-based painter Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920) blazed a trail like a comet across the early 20th-century art landscape during his short lifetime. It’s no exaggeration to say there were few like him and that his work brought dazzling modernity to the art world. He remains a star who burned brighter than most and whose work gained greater prominence as a result of his early death at age 35.

And now comes Nu Couché (Sur le Côté Gauche), which premiered in Hong Kong last month and is due to be auctioned at the Sotheby’s Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale in New York on May 14. The work, from 1917, carries the highest estimate ever placed on an artwork – US$150 million. Leonardo da Vinci’s recent record-breaking Salvator Mundi carried a pre-sale estimate of just US$100 million, though it ultimately sold for US$450 million in November 2017.

There are 22 paintings in Modigliani’s suite of nudes, the majority of which reside in museums in the US, England and China; only nine remain in private hands, thus making them incredibly rare. Nu Couché was previously owned by casino mogul Steve Wynn and is now coming to the market via the hands of Irish billionaire and horse racing tycoon John Magnier. Among the striking things about this work is that it’s Modigliani’s largest canvas and, at 147 centimetres across, it’s the only one of his nudes to contain the entire figure in the picture – the artist frequently didn’t show the hands or feet. Recently shown at the Tate Modern’s retrospective of the Italian artist’s work in London, it was described as the “cover star” of that exhibition.

Read More

The nude series was initiated in 1915 by Modigliani’s dealer, Léopold Zborowski, who offered a space and paid the models. Zborowski paid the artist a stipend of 15 francs per day and the models five francs each to pose in an apartment just above his own at 3 Rue Joseph Bara. On the works’ public debut in 1917 – which was, notably, Modigliani’s only solo exhibition during his lifetime – the striking images stopped traffic (quite literally) and prompted police to close the show on opening day.

Despite the form of the nude being a classic theme throughout art history, Modigliani made his radically innovative. The sexuality is supremely confident, self-possessed and proud. Simultaneously, Nu Couché fuses centuries of visual culture – the linear simplicity of African statues and their carvings, Japanese art, Egyptian and Greek antiquities, Renaissance frescoes and Mannerist painting, as well as the cutting-edge earth-toned palette and geometric modelling of Cubism by way of his Parisian contemporaries.

In Modigliani’s case, his was a glamorous set of creative cohorts. After graduating from art school in Florence and Venice, he moved to Paris in 1906, where he lived in Montmartre and then Montparnasse. After meeting his first buyer, Paul Alexandre, in 1907, he first exhibited his work in 1908 at the Salon des Indépendants. Influenced by Paul Cézanne and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Modigliani’s layout became stronger and his lines more accentuated. By 1909, he had met Constantin Brâncuși, who inspired in Modigliani a love of sculpture, through which he produced a series of heads. He also met Pablo Picasso, Guillaume Apollinaire, André Derain and Diego Rivera during this period.

For the remainder of his career, Modigliani spent most of his time on portraits of his young common-law wife, Jeanne Héburterne, and his friends – in search of an abstract, ideal beauty. However, as his alcoholism and drug addiction continued the downward spiral, Modigliani, who had battled tuberculosis since contracting it at age 16, ultimately succumbed to the disease and died in 1920. (Tragically, Héburterne, eight months pregnant with his child, committed suicide the next day; she was only 21.) “I want to live a short, intense life,” Modigliani had said. He left behind about 350 paintings.

Modigliani’s brief, frenzied light has never burned more brightly than now, as the artist’s reputation and work have been on the ascendant. Nu Couché was acquired by its present owner at auction in 2003 for US$26.9 million. In 2015, another reclining nude (perhaps the artist’s most voluptuous) from the series sold at auction for US$170.4 million to the owner of Shanghai’s Long Museum, Chinese collector Liu Yiqian, which at the time made it the second-highest price ever paid for a work of art at auction.

“There is the nude before Modigliani – and there is the nude after Modigliani,” says Simon Shaw, the worldwide co-head of Sotheby’s Impressionist & Modern Art department. Expect Nu Couché to stop traffic once again when it leads the evening sale in New York. Do we hear US$200 million-plus, making it the world’s second most expensive work at auction? Will it surpass Salvator Mundi? Going, going… gone.

![]()

Image: courtesy of Sotheby’s

Back to top

Field of Dreams

A little Cézanne with a large reputation goes to auction this month, courtesy of Hong Kong-based auctioneer and gallery Macey & Sons

Field of Dreams

A little Cézanne with a large reputation goes to auction this month, courtesy of Hong Kong-based auctioneer and gallery Macey & Sons

Culture > Art |

Field of Dreams

April 6, 2018 / by China Daily Lifestyle Premium

Image above: La Vie des Champs, 1876–77

Jonathan Macey of Macey & Sons

On April 29, Hong Kong boutique auctioneer and gallery Macey & Sons will auction Paul Cézanne’s La Vie des Champs (Life in the Fields), in connection with Philadelphia auction house Freeman’s. “We are honoured and delighted to be able to share this rarely seen Cézanne painting with our clients and friends prior to its upcoming auction in Philadelphia,” says Jonathan Macey, founder of Macey & Sons. The work is estimated between US$1.2 million to US$1.8 million.

Painted in 1876 and 1877, La Vie des Champs, an oil that measures 11 by 14 inches, displays five figures among the trees, with a couple from Nice on the left and a woman with a jug atop her head in the centre of the image, more redolent somehow of Gauguin’s Polynesia than Cézanne’s Provence. We also discern a villa high on a hill in the background. The painting came at a time when Cézanne was obsessed with landscape – the famous Mont Sainte-Victoire dominates 44 of his oil paintings and 43 watercolours.

The rare work belonged to Dorrance “Dodo” Hamilton, the Campbell Soup heiress who died last April at the age of 88. The granddaughter of John Thompson Dorrance, a chemist who invented a method for condensing soup, Hamilton was a prominent cultural and philanthropic figure in Philadelphia. She was also a keen horticulturalist – a recreation that seems to have dictated much of her art portfolio. Hamilton collected what she liked, rather than with an eye on the market.

Read More

This all adds provenance to a work already bursting with history. One of many champagne moments the picture has is that it once belonged to French dealer Ambroise Vollard. From there, it changed hands to Prince Alexandre Bibesco, a Romanian aristocrat who befriended Marcel Proust; the painting was eventually purchased by Elinor Dorrance Ingersoll, Hamilton’s mother.

Vollard was a legend in his lifetime and beyond. In 1887, at the age of 29, he arrived in Paris from Réunion, a remote French island colony east of Madagascar, and made his mark as a dealer when he staged Cézanne’s first solo show in 1895. The painter had been living in obscurity in Aix-en-Provence in the south of France and his work hadn’t been exhibited in more than 20 years. Vollard found Cézanne and bought more than 100 of his canvases. (The artist was 56 years old at the time.) The exhibition was a huge success – and Cézanne’s place in the pantheon of modern art was set.

The Card Players, 1892-93

Matisse cobbled together every last franc he could find to buy a Cézanne and even young Pablo Picasso was mesmerised by the painter. Without Vollard’s exposure of Cézanne, the school of what we now know as cubism might never have existed. Picasso remarked that his style was heavily influenced by Cézanne (who he called “the father of us all”) and it was at Vollard’s gallery that he first laid eyes on the artist’s work. Like his fellow post-impressionists Gauguin and Van Gogh, Cézanne was thought to have improved immensely as he got older. His early pieces fall somewhere between Delacroix and Guercino, but his later work marks a dramatic shift.

In his lifetime, Cézanne paid the price for being a pioneer in the art world. He withdrew from Paris to his hometown of Aix-en-Provence; there, in isolation, he studied the perceived problems of art. Like Degas, he didn’t have financial concerns and could therefore indulge, applying exacting standards to what he produced. And while he enjoyed the work of the impressionists in conveying nature, he felt that paintings of nature should not be aimed at copying an object, but realising one’s sensations.

Not all artists liked impressionism. Some felt painting that was simply pleasing to the eye lacked in substance. But Cézanne felt that order and balance had been lost as artists sought the fleeting in-the-moment experience, ignoring the enduring forms of nature. He desired a simplification of natural forms into geometric essentials.

Van Gogh agreed; he thought by exploring nothing but optical qualities of light that art was in danger of losing its intensity and passion. And Gauguin famously went to Polynesia to address the issue. What we call modern art grew out of feelings of dissatisfaction; Cézanne’s approach led to cubism and Picasso, Van Gogh to expressionism that went on to influence the Germans, and Gauguin to primitivism.

Much of Cézanne’s life was dominated by his association with the novelist Émile Zola. They met as schoolboys and became lifelong friends, exchanging numerous poignant letters, until in 1886, the artist angrily parted ways following the publication of the author’s L’Oeuvre. Cézanne thought Zola had based the protagonist, Claude Lantier, on him – the narrative depicts the failure of an artist, a lost genius who, powerless to create, ends up committing suicide.

Of course, Cézanne’s reality turned out much different. One of his paintings from The Card Players series sold for US$250 million to the royal family of Qatar in 2011, making it the second most expensive painting ever sold.

The letters Cézanne left behind are among art’s most touching reads. Five years prior to his death, he wrote to the artist Gustave Heiries in 1901: “I have perhaps come too soon. I was the painter of your generation more than my own. You are young… As for me, I’m getting old. I won’t have time to express myself. Let’s get to work.” To his son, Cézanne wrote: “Have a little confidence in yourself, and work. Never forget your art, sic itur ad astra [“thus one reaches the stars”, from Book 9 of the Aeneid].”

La Vie des Champs is a vision to living, feeling, sensation and ambition, and the dynamic epicentre of art at the dawn of its modern crossroads.

![]()

Images: Provided to China Daily by Macey & Sons

Back to top

Get Real

Chinese artist Yu Hong brings her poignant canvases to Art Basel in

Hong Kong

Get Real

Chinese artist Yu Hong brings her poignant canvases to Art Basel in

Hong Kong

Culture > Art |

Get Real

March 2, 2018 / by China Daily Lifestyle Premium

Image above: Yu Hong

A New Century 《新世纪》

When New York City’s Solomon R Guggenheim Museum presented its extensive survey of Chinese contemporary art, titled Art and China After 1989 (held from October 2017 to January 2018 and now running at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art), one of the works showcased was from Yu Hong’s Witness to Growth series. It’s an image composed of two parts; one shows Yu cutting her hair in her dormitory room, a somewhat banal event, while next to her is a newspaper clipping of Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping on his tour of Guangdong as part of the reform and opening-up policy. Yu has made a habit of painting herself at different stages of China’s economic and cultural evolution, and juxtaposing her work with newspaper reality. “Against the backdrop of a nation-state’s grand narrative, the quotidian details of our tiny individual lives are all the more important,” she explains.

A man playing the hula hoop 《玩呼啦圈的男子》

Nobody does the seemingly trifling or random happenstances of daily life in the world’s largest country better than she does. Born in 1966 in Xi’an, Yu is the star of realism in China’s art world. “My work consists mostly of realist paintings concerned with human growth, the human condition and the various problems we face,” she says. Noting that China has changed so dramatically in the past 30 to 40 years, she says in this era of change she is “first an observer” – as she lives right in the middle of the change. She began the Witness to Growth paintings in 1999, after the birth of her daughter. “She was like a blank page, and as she grows up, it’s up to society to inscribe this blank page,” recalls Yu. So she has painted one set per year since, juxtaposing the personal against the national. The series represents “personal growth and social development”, she says, going on to describe them as “pulsing systems that infiltrate and interfere with one another, against the backdrop of a nation-state’s grand narrative”.

All of which can be seen when she brings her solo exhibition to Art Basel in Hong Kong this month with Beijing’s Long March Space, which will feature selected works from different creative periods of the artist. The show contains works such as A Man Playing the Hula Hoop (1992), made as part of the New Generation movement in the 1990s, and her most recent large-scale project A New Century (2017). As well, there are pieces from her previous major solo exhibitions, including Witness to Growth (2002 and 2007), Golden Sky (2010), Golden Horizon (2011), Wondering Clouds (2013), Concurrent Realms (2015) and Garden of Dreams (2016). This seemingly boundless diversity of work encompasses not only Yu’s paintings, but also her explorations on silk, glass, tinfoil, and other surfaces and materials.

Complementing the exhibition is director Wang Xiaoshuai’s Days Gone By – Yu Hong (2009), which will be screened at Art Basel in Hong Kong’s film sector. It’s a companion piece to Wang’s directorial debut The Days (1993), which stars Yu in the female lead. The movie tells of a different reality in the artist’s life, echoing her portrayal as a young artist in The Days yet showing how her role has changed many years later – as a wife and mother who’s busy with her own career and family, with responsibilities to her school and society. Yu and curator Alexandra Munroe, who brought together the show at the Guggenheim, will attend the post-screening discussion.

Read More

In addition, Yu’s most recent artistic expression, She’s Already Gone (2017), a virtual reality project in collaboration with Khora Contemporary in Denmark, will be included in Art Basel’s Kabinett sector. In this work, the viewer is placed in the position of a female protagonist, traversing through four different eras: the Neolithic Hongshan culture, the Ming Dynasty, the Cultural Revolution and contemporary times. Some of the scenes come from the artist’s personal life, filling the work with an intriguing exchange between affairs both virtual and real. Through this process, history and individual life mix with each other, repeat and change.

Night Scene《夜色》

Yu studied oil painting at Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) and received a postgraduate degree from the department in 1996; she’s been a teacher there since 1988. From the start, Yu was trained in realist painting, which over time would translate into her own individual aesthetic language. The core subject of her paintings has always been human nature, and the way human beings grow and exist in society. If China had an equivalent to England’s LS Lowry, then Yu might be it.

The spirit of Yu’s creation most often arises from her personal life and the surroundings of quotidian existence, constructing a world which ingeniously fuses together perceptions of time and memories through art, as well as adeptly seizing the sporadic evolution of the emotions of human self-experience. The Witness to Growth series acts as a sort of record of life, while touching upon the current events of each year. Yu often uses existing images as a starting point for her art, taking photographs and her own point of view to create compositions and rearrange them in renewed combinations that emphasise the objective way in which pre-existing images can be reused and strengthened in new compositions.

In the Gold series (2010–11) of paintings, this feeling for form takes on its most poetic level. Yu’s intensive studies into the traditional Chinese paintings of Dunhuang, the murals of the Kizil Cave complex and Western painterly traditions take form, interweaving a sensitivity towards art history traditions and contemporary daily life. For Wondering Clouds (2013), Yu interviewed six people about their internal states and their personal histories, all revolving around the topic of anxiety. By so doing, Yu was attempting to express not only their individual sorrows, but to share the universality of the experiences of human beings in society and to understand the core of people’s depressions. Executed around the same time, On the Clouds (2013) was an attempt by the artist to combine a spatial concept with the landscapes of daily life, using a more theatrical method of expressing the uncertainties with which life is filled.

A turning point in Yu’s career seems to have ensued with Concurrent Realms (2014–15), a series of works floated into a world of fantastic fables and reality. Here, she combines seemingly disparate nations, regions and cultures to form a single entity. Such can be seen in her most recent work, A New Century (2017), in which she blends both macro and microscopic perspectives, highlighting the circumstance of being an individual within a larger group. Today, the student cutting her hair in her dormitory from Yu’s early career has become a photographer, perched atop the clouds to capture one of the most repeated images in Western art – The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo, part of his masterpiece which graces the Sistine Chapel ceiling. China as window on the world and Yu’s view of it: subtle, elegant, parochial and compelling.

![]()

Images: Yu Hong; courtesy of Long March Space

Back to top

Romance of Spring《春恋图》

Falling Apart

German artist Magnus Plessen contemplates the Great War and the human body

Falling Apart

German artist Magnus Plessen contemplates the Great War and the human body

Culture > Art |

Falling Apart

March 2, 2018 / by China Daily Lifestyle Premium

It’s been four years in the making: German painter Magnus Plessen is finally exhibiting a selection of new paintings, drawings and collages from his evolving 1914 series for the first time in Hong Kong. Inspired by German pacifist Ernst Friedrich’s influential 1924 photobook War Against War, Plessen depicts the First World War and the devastating effect it had.

War Against War was the first major publication to reveal the appallingly destructive effect of automatic weapons, with real images of mutilated soldiers and dreadful killing scenes. The survivors depicted in the photos face the camera directly – with dramatically damaged faces, empty eye sockets and missing legs. These images, nearly a century old, gave the painter a shock and drove him to contemplate the mechanism of the human body.

In Plessen’s series, the wounded soldiers are restored with new facial expressions and prosthetic limbs, painted in contrasting colours and black square blocks, with fluid, gentle brushwork in warm beige, pastel blue and rose pink. The fragmented body parts of heads, thighs, breasts and feet float around the space, seemingly looking for a place to be fixed.

Read More

The intriguing title of the exhibition, Mess Dress Mess Undress, is actually a wordplay of many layers. “Mess” can either refer to where the soldiers congregate and socialise, or the unwanted situation of disorder and confusion, whereas “dress” aligns with the artist’s aesthetic refinement as to “dress up” what has been collapsed and cover the “messed-up”.

For some of his paintings and paper collages, Plessen rotates the works 90 degrees during the production. This creates distance for the artist and disrupts his relationship with the object. It also fosters a disconnect between physical reality and the imagination.

Visit White Cube to see Mess Dress Mess Undress through March 17; admission is free.

![]()

White Cube Hong Kong

Address: 50 Connaught Road C, Central

(whitecube.com)

Images: ©Magnus Plessen; courtesy of ©White Cube

Back to top

In Her Own Write

With Iran set to be represented at Art Basel Hong Kong for the first time in March, get to know Tehran-based artist Golnaz Fathi, who has turned traditional Persian calligraphy into an abstract art form

In Her Own Write

With Iran set to be represented at Art Basel Hong Kong for the first time in March, get to know Tehran-based artist Golnaz Fathi, who has turned traditional Persian calligraphy into an abstract art form

Culture > Art |

In Her Own Write

March 2, 2018 / by Joël Fischer

Part of the wave of Iranian artists enjoying increasing international recognition, Golnaz Fathi has turned a childhood passion into a highly individual art form. She became fascinated by calligraphy when she was growing up in Tehran and reached the very top of the craft when she graduated from the Iranian Society of Calligraphy in Tehran in 1996 after six years of study. She then turned to her first love, art, and has developed her own unique style, which incorporates her mastery of calligraphy.

Speaking from her Tehran apartment, where the walls are adorned with her distinctive paintings, Fathi explains the progression of her art. “As the years have passed, my work has become pure abstract – I am a choreographer and these are my dancers,” she says, referring to the calligraphy characters. She uses two contrasting techniques – one with acrylic paint and brush, which she says is similar to the “action painting” pioneered by the American abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock, and another with a very fine pen that produces a result of layers of hundreds and hundreds of lines.

Fathi’s first solo exhibition in Mainland China was at the Pearl Lam Galleries Shanghai in 2013, when she and renowned Chinese calligrapher Wang Dongling created new works in a joint “art performance”. Although they could only exchange limited words in English, the artistic bond proved to be more than an adequate substitute for verbal communication – Wang has his own abstract style of what he dubs “calligraphic painting”.

Read More

“It was fabulous, a cultural bridge,” says Fathi. “We did six works together at the gallery in front of an audience – some of them I started, some of them he started, and the other one added to it to finish.” While she says the Persian and Chinese calligraphy styles are quite distinct, they have one important thing in common: “The kind of dedication you have to give to become a master is quite the same. You cannot become a calligrapher if it is just a hobby – it should be your life.”

Fathi is holding a second exhibition in Shanghai in May; gallery owner Pearl Lam explains: “I like to work with artists who can surprise me and make me think differently about art and life in general. Golnaz is such an artist.” And turning calligraphy into an art form? “Calligraphy is prized as a form of self-expression and self-cultivation; the principles behind it are still relevant to art today.” She adds that many artists in China are “reinterpreting traditions, especially ink-brush painting and Chinese abstract art”.

Lam says that the Chinese market is becoming increasingly receptive to artists from different backgrounds, such as Fathi. “Art can act as a bridge between cultures and facilitate communication through the exchange of ideas,” she explains. “By understanding another culture’s art, one can better understand how they live and think, which also reflects on one’s own culture through the similarities and differences.”

The Tehran-based Dastan’s Basement is the first Iranian gallery to participate in Art Basel Hong Kong, which runs from March 29 to 31 at the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre.

![]()

Images: courtesy of Golnaz Fathi

Back to top

New Masters

American art dealer David Zwirner opens his inaugural Asian space in H Queen’s with a solo exhibition by Belgian painter Michaël Borremans

New Masters

American art dealer David Zwirner opens his inaugural Asian space in H Queen’s with a solo exhibition by Belgian painter Michaël Borremans

Culture > Art |

New Masters

January 26, 2018 / by Michael Liu

The man with the Midas touch in matters of art, Cologne-born, New York-based gallery owner David Zwirner is consistently listed as one of the most powerful art dealers in the world. But he’s only just taken the plunge in Asia by opening his first space in Hong Kong, on the backs of his acclaimed galleries in New York and London.

Situated in the William Lim-designed H Queen’s on Queen’s Road Central, Zwirner has taken over the fifth and sixth floors of the innovative new gallery and lifestyle glass tower. Zwirner’s 10,000sqft gallery space has been overseen by

Annabelle Selldorf, who also created the art dealer’s other outlets in Manhattan and Mayfair. The space features four adaptable, column-free exhibition spaces that can be appropriated to suit a variety of artworks.

The Hong Kong opening coincides with the 25th anniversary of Zwirner’s gallery in New York, an occasion for which there will be a special exhibition by artists who have shaped the gallery since its founding in 1993 – among them Dan Flavin, Luc Tuymans, Donald Judd, William Eggleston, Jordan Wolfson and more.

Part of this illustrious stable of talent is Belgian painter Michaël Borremans; his latest series, Fire from the Sun, marks Zwirner’s inaugural exhibition in Hong Kong and the artist’s first solo show in the city. The exhibition, which opened on January 26, is accompanied by a catalogue and a new essay by distinguished art critic, curator and cultural historian Michael Bracewell.

Read More

A critical darling and the heir apparent to Francisco Goya, the Ghent-based Borremans paints enigmatic portraits that suggest a dark, sinister narrative lurking in the depths. His haunting canvases reference the Old Masters and numerous moments in art history, steeped in ambiguous symbolism. It’s a world where the beauty of the Romantics meets the aggressive, sexually charged brutality of the modern era in silent meditation.

To support the Hong Kong gallery launch, Zwirner has appointed Asian art experts Leo Xu (who founded Leo Xu Projects in Shanghai in 2011, which represented emerging Chinese artists) and Jennifer Yum (the former vice-president and head of morning day sales in the post-war and contemporary art department at Christie’s New York) as directors to oversee his first outpost in the region.

Prior to opening his gallery, Xu was the Shanghai director of the James Cohan Gallery and the founding director of Chambers Fine Art in Beijing. During her 12 years at Christie’s, Yum actively developed business in Asia, particularly in South Korea and Japan. For nearly a decade, she was the principal of Jennifer Yum Art Advisory, specialising in advising private, corporate and institutional clients on art acquisitions, appraisals and curatorial management.

Clearly we’re getting 2018 started on the right foot, artistically speaking.

![]()

Images: © Michaël Borremans

Back to top

Lost Arts

Sculptor-jeweller Dominique Favey Blackmore’s baroque style combines the subtlety of lost-wax casting with the roughness of sculpted metal – and her unique creations have won over couturiers and collectors worldwide

Lost Arts

Sculptor-jeweller Dominique Favey Blackmore’s baroque style combines the subtlety of lost-wax casting with the roughness of sculpted metal – and her unique creations have won over couturiers and collectors worldwide

Culture > Art |

Lost Arts

December 1, 2017 / by China Daily Lifestyle Premium

Since creating her first piece of “jewellery as art” for her mother in the 1980s at the age of 16, Dominique Favey Blackmore has made thousands of pieces. Today, her limited run of baroque-style rings, necklaces, earrings and bracelets are worn by celebrities and royalty around the world.

Following in the footsteps of her father, Blackmore studied sculpture at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, with surrealist sculptor Isabelle Waldberg as her mentor. She was still a student when designer Paco Rabanne asked her to contribute to his new haute couture collection – and this proved to be her baptism by fire.

“His sculptor was ill and I stepped in to take his place,” she recalls.“I didn’t know how to weld, but I worked night and day with my friends from Beaux-Arts and the wager was won. We turned out some incredible pieces.”

The collaboration ended up lasting more than 10 years; technically and creatively, each collection represented a new and extreme challenge: “I made Mary Queen of Scots collars, draped pieces and bustiers in metal lace.”

During this period, Blackmore also worked with Emanuel Ungaro and Christian Lacroix. The jewellery and adornments she conceived for their fashion shows – as well as for her own creations – combined the subtlety of lost-wax casting with the rough effect of welded metal.

Very few sculptors are able to master the former technique, which starts by making a plaster mould around a wax model; the mould is then heated to around 800°C. The wax melts and runs out, and molten metal is poured into the empty space that remains. Once the whole thing has cooled, the plaster is broken and the metal piece is removed, cleaned and chiselled.

Blackmore is also one of the few jewellers to work pieces of antique lace into her creations. “I incorporate them into my wax models, then I cast them in bronze, silver or gold with the lost-wax technique,” she explains.

Pieces are generally one-of-a-kind, though some are made in a limited series of no more than eight. Most of her loyal customers have the privilege of discovering the latest collection before everyone else, through an exclusive preview at the jeweller’s Paris workshop.

What’s ahead for Blackmore? “The 2018 collection will be very much about the sea, with lots of seashell prints for the lost-wax pieces and crustaceans for the welded metal ones,” she confides.