People > LP Exclusive |

A Year and A Day with Dylan

May 27, 2016 / by Robert Jones

How did it all begin?

I first discovered Bob Dylan when he was doing a TV variety show in February of 1964 – I didn’t know who he was, I didn’t know much about folk music, but he started singing “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll”. Those words were so mesmerising for me, as poetry, and so scary; here was this young fellow singing these things publicly about this crime. I was hooked on the idea and the words.

Why did you want to photograph him?

I was a young photographer and wanted to build my portfolio, so I called his management office and asked for an hour’s sitting to do a portrait. A half a year went by before accidentally I got Albert Grossman [Dylan’s manager] on the phone and he said, “Why don’t you come up to Woodstock next Thursday?” And that’s how it started.

He seemed very playful – climbing a tree, sitting in a swing. Was that typical of the young Dylan?

Dylan didn’t care to just do a portrait; he wanted to do more interesting pictures. He scampered up a tree – physically he was pretty strong, he was in good condition – he snapped a bullwhip in the air. He felt he should do things he normally does and that I should photograph it. And I just took pictures and I realised he was giving me something. Then he said, “Do you want to go for lunch?” and my hour turned into five or six hours.

Read More

What happened next?

I drove back to New York. I made prints. I made an appointment and went up to the office in New York, and met with his manager Albert Grossman and Bob, and put the pictures out on a big conference table. They walked around the table. They looked at the pictures and then Bob said to me “I’m going to Philadelphia next week; would you like to come?” and I said yes, and that’s how it all began.

Do you think Grossman and Dylan saw you as part of the process of creating his public persona?

I did some pictures of him performing when we went to Philadelphia – I was enthralled because his stage performance was very powerful. I gave him some pictures up at the office of that shoot, and the next time we went to a concert a couple of weeks after that there were posters at the theatre with those pictures. And when they had to do an advertisement, they would call me for pictures. They liked one where his hand was to his face – that picture they used around the world, and it was one of the pictures that people met him by, knew him by, at the beginning of his career when he was becoming an international star and the guy who changed the music business.

Your cover photo of Bringing it All Back Home showed Dylan’s change to a new rock-star image.

Bringing it All Back Home was the first album cover I ever did and he doesn’t look like the guy in the first four albums. He’s not a folk singer in that picture; you don’t know what he does. I wanted to show that he was a prince of music – that if music had degrees of royalty, he would be a prince. I was certain, with all the music I was hearing, all the poetry, everything, that he was a special person, a creator, an artist. And I wanted him to look that way.

Your images seem to perfectly capture where Dylan was as an artist at that time.

That was my strength as a portrait photographer – taking a portrait means you delineate, try to show the audience something of this person that may even be a little below the surface. Something of the personality, something of the moment – and some mystery. All these things go into great portraits.

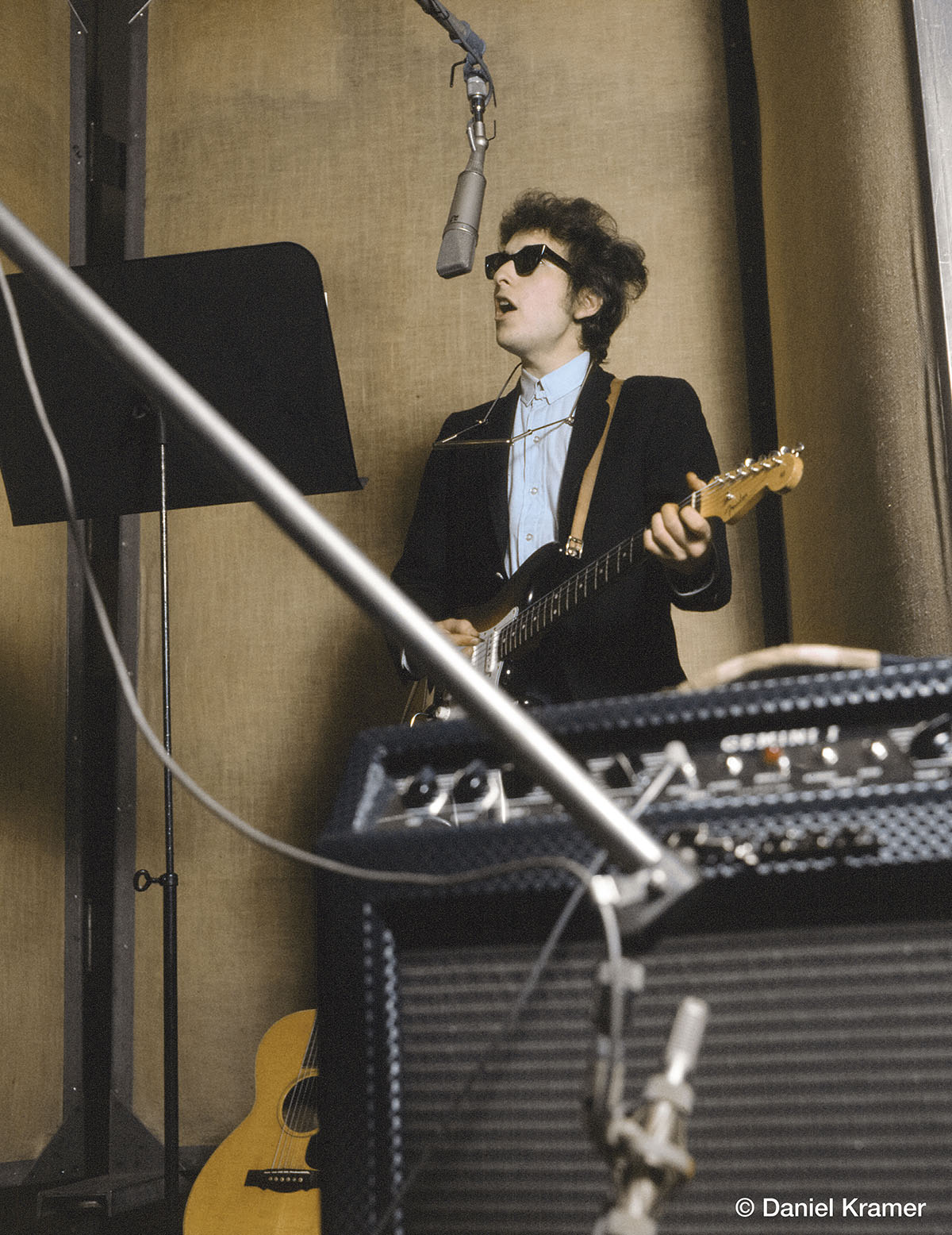

Did you have a sense of musical history being made when you photographed the Bringing it All Back Home recording sessions?

No one had heard this music before. Bob had written his songs for the session but no one had heard his music, his idea for the music. That was the first time he professionally played electric since he had become Bob Dylan. He was trying to make combinations, trying to work things out. This music, folk rock as it became known, was being invented right there in Studio A while I was shooting.

In the book you describe his creativity like a “spring” that was about to uncoil. Why?

I sensed he was anxious to get it out, anxious to show what he could do, anxious to make a good album, anxious to get everyone in line so they could work with him, anxious to do these things and he was putting forth this effort. He was the same guy who scampered up the tree: you saw his strength, a different strength – the strength of conviction, the strength of his musicianship. The coil idea was that this was in him, and by releasing it in these sessions he was becoming Bob Dylan, the Bob Dylan that we learned to know. He was becoming that, right there, in the studio. And it was very exciting.

You were shooting images in the studio the day he recorded “Like a Rolling Stone”, which many critics rank as the greatest rock song ever. What were your first impressions?

You knew it was different and you knew it was special because of its length, but you didn’t know more than that. When the thing is being created, you know it’s new, but you don’t know yet what we’ve got or how will people accept it, or will they actually run it, because songs were three minutes – that’s the length they played on the disc jockey shows.

You saw the length as a problem?

Three minutes was the average for a song, which was why there were 12 songs on an album because the 12-inch vinyl held that much music in its grooves; you could put six on each side. It was all part of the arithmetic, and here comes this guy and it’s six minutes and something – will they even play it? Will they say you have to edit it down? Will Columbia Records say, “We have to cut this in half, Bob. We can’t put it out this way; it’s not right. Nobody makes them this long.” It was daring – and successful. It changed that day. After that, there was no going back. Not for him and not for the music industry. It changed. That song.

What’s the story behind the Highway 61 Revisited cover where Dylan wears the Triumph Motorcycles T-shirt?

We spent a lot of that day shooting at this cafe, O Henry’s. I had made a lot of pictures and I reckoned we probably had the cover in there. Then we walked a few blocks to where Bob was living at the time in Gramercy Park and he said, “Look, I have a new T-shirt and I’d like to get a picture of me in it.” So Bob went into his room and came out with this T-shirt on and a colourful shirt over it, and sat down on the step.

Who is standing behind him?

There was a big hole in the top left of the frame, so I said to his road manager Bob Neuwirth, “Why don’t you go up and stand behind Bob?” You see him from the waist down but you don’t know who he is. Then I asked my assistant to give him my other camera, and I asked Bob Neuwirth to hang it from his hand. It looked good, so I took two frames and said, “Okay guys, we’re finished for today.” When I edited all the stuff, Bob said, “I like this one, let’s run with this.”

This was much different from Bringing it All Back Home; there was no script. They were made in two different ways and they both worked.

There is a very intense image of Dylan and Johnny Cash deep in conversation at a dinner table. What was the dynamic between them?

It is summed up in a picture where they are standing together for a portrait and Cash has his arm around Bobby’s shoulder. Big, tall, strong – he is the older man and he is the more famous man at the moment – he is the Man in Black. Bob and him had a good relationship, a friendly one; they wrote to each other. I felt there was the older, more experienced performer and the young, coming-along troubadour.

You seemed impressed by Johnny Cash’s presence.

When I met him, I had already met the president of the United States. I had already met Marilyn Monroe. I had already met Muhammad Ali. Meeting Johnny Cash – you knew he was a star, even if you didn’t know anything about him. He had it in him and it was oozing out. He filled up the whole room. He was special and you sensed it right away. There are people like that. He was a little overwhelming.

Do you feel you got close to Dylan?

I think that the pictures tell the story. We were able to work together. We trusted each other to a point. We both wanted the same thing. We wanted good images, good pictures; we wanted a document. That’s what we were doing. I think we were successful at it. Most of the things in this book are honest.

You shot around 30 sessions with him over a year and a day – from August 27, 1964 to August 28, 1965. Why did it end?

I felt I had gone from point A to point B and obtained everything. I had recording, I had stage, I had home, I had private, I had the album cover shots, a lot of stuff and it’s a big world. I thought I had done my work. Bob had a nice collection of stuff to use, and soon after that he had a motorcycle accident and he was out of commission for a very long time. He was unseen, he was getting married, he was having children, and I had to move on just like he had to move on.

You first published a pocket-sized photo book of Dylan in 1968. Why publish this deluxe edition now?

In the first book, there were not many of the other people – Johnny Cash, Allen Ginsberg. The first book had 140 pictures; it was much more limited. So why another one? There were these other pictures that would flesh out the story and maybe get another take on it. And also there are a lot of people who don’t know there is a first book, who weren’t even born then. So this is the updated edition.

Have you met Dylan since?

One of the things I try not to do, about Dylan or my other subjects who kindly let me into their lives, is to discuss them as a private person. I have worked with Dylan’s organisation for these 50 years and I just provided 40 pictures for the book that went with his album The Cutting Edge. I have always been involved with one project or another that Bob was working on. So it is a continuing relationship.

Could you have imagined that Dylan would still be performing well into his 70s?

I certainly thought that Dylan’s career would not be over in six months.

I certainly realised he had some kind of musical genius that still hadn’t really blossomed or flourished the way it eventually did; it just kept building and building. There are a lot of special people out there, but he was special special.

![]()

Daniel Kramer. Bob Dylan: A Year and a Day

Edition of 1,765 + 200 APs

Daniel Kramer

Hardcover in a clamshell box, letterpress-printed chapter openers with tipped-in photographs, two different paper stocks, and three foldouts, 31.2 x 44cm, 288 pages

ISBN 978-3-8365-4760-4

ultilingual Edition: English, French, German